On the Road Again: Trailers

By Dave

Weinstein

Summer 2007

With a

renaissance underway, broken-down travel trailers return to reclaim their

modernist roots

They're small, sleek, and often silvery-skinned, superbly

engineered, and with zero wasted space. People can live in them and, when it's

time to move, can move in them. The best among them are stylish, even

beautiful. More than anything Le Corbusier ever designed, they are true

'machines for living.'

They're small, sleek, and often silvery-skinned, superbly

engineered, and with zero wasted space. People can live in them and, when it's

time to move, can move in them. The best among them are stylish, even

beautiful. More than anything Le Corbusier ever designed, they are true

'machines for living.'

Yet in

architectural history, mobile home travel trailers get no respect.

Architectural

historians brag about the profession's commitment to mass-producing houses for

the poor and working class—an effort that has been much promised but rarely

achieved. Richard Neutra won praise for his low-cost

World War II housing in San Pedro, Gregory Ain for

his Mar Vista tract in Venice, aimed at ex-GI's with young families. Yet

architectural historians never include travel trailers in their paeans to

'social housing.'

But

throughout the Depression and in the immediate postwar years, thousands of

Americans found shelter in simple, efficient, and inexpensive travel trailers.

Trailers were, quite simply, a form of vernacular, working-class modernism

inhabited by people who had never heard about 'form and function.'

It is

true, of course, that trailers are not technically houses—nor, in some views,

architecture at all. Their designers remain largely anonymous. Trailers don't

fit in the standard architectural paradigms. There is no theory of trailers.

Like tract houses, which have also been excluded from much of architectural

history, trailers are not quite respectable. They're a form of 'low art' at

best, associated with 'trailer trash,' at one end of the spectrum; and with

lower-middle-class vacationers wearing plaid shorts at the other. Despite their

streamlined look, there's something about trailers that can seem irredeemably

square.

Trailer

fans, however, are taking heart, because trailers are starting to gain

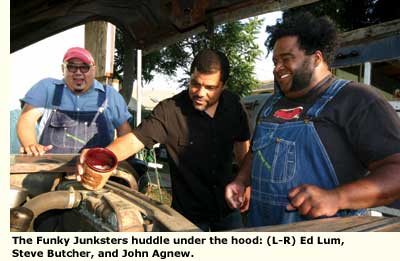

attention among architects, historians, and the common herd. "These

trailers were the original small living spaces," says Ed Lum, a graphic

designer and trailer aficionado who's as square as a jellyfish. "Now it's

come back that people are looking for small living spaces. So what was retro is

now modern again." Lum lives in a trailer in what may be the country's

only trailer park that has been declared a historic monument, Monterey Trailer

Park in Los Angeles. "A lot of architects are now getting into this,"

he says. "They're recognizing them a lot more than they used to."

California,

not surprisingly, is in the forefront of the travel trailer renaissance. In Los

Angeles, architect Jennifer Siegel, who owns an Airstream trailer, designs

prefabricated homes and offices on wheels through her firm, the Office of Mobil

Design. And artist Andrea Zittel, who's based in

Joshua Tree, in the high desert east of Palm Springs, has created many

trailer-like art objects—including the tiny 'A-Z Escape Vehicle' ("a

refuge from public interaction") and the 'A-Z Wagon Station' ("an

evocation of the Old West covered wagon") that are more thought experiments

than marketable products.

In her

art, Zittel poses the question: how small can a space

be and still be considered a 'home'? That's a question trailer manufacturers

have been trying to answer since the 1920s. Perhaps the best way to trace their

efforts—and to find out just how modern travel trailers can be—is to visit

Funky Junk Farms, a collection of vintage trailers and more, at two sites in

Southern California.

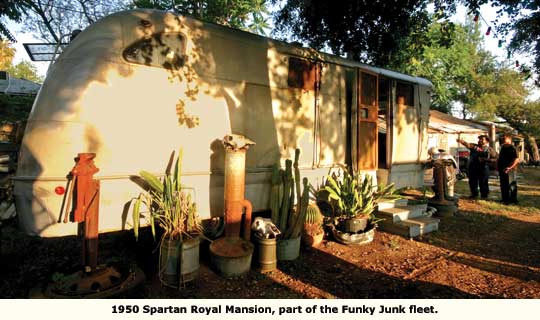

"Look

at them," says John Agnew, the proprietor of the farm's main 'campus' in

Altadena, which is filled with trailers of varied sorts in varied stages of

repair. "They're beautiful. They're like big bungalows on wheels."

At the

farm, a former tropical fish hatchery called the Altadena Water Gardens, Agnew,

Lum, and their friend Steve Butcher collect, preserve, worship, and restore

vintage trailers. Butcher, whose background is in vintage auto restoration,

also runs a large indoor trailer rehab hospital in the Ventura County town of

Fillmore, an hour away.

Agnew's

Funky Junk Farms is both a museum and his home. The operation is part hobby,

part obsession, and not quite all business. "These are art pieces to

us," he says. "This is a gallery."

Agnew

and Butcher are Teamsters who drive prop trucks and other vehicles for the

movie studios. They met on the set of 'Pontiac Moon,' with Mary E. Steenburgen

and Ted Danson, discovered a shared interest in old

cars and other examples of antique Americana, and were soon searching out

trailers and other treasures every weekend. Lum came into the picture when

Agnew noticed his girlfriend's cool old Rambler sedan parked outside a coffee

shop.

Funky

Junk rents its trailers to the studios for movies, TV shows, and commercials.

If the studios need authentic Art Deco cigarette machines, shelves filled with

1930s cleaning products, or handmade robots from the 1950s, Funky Junk's got

that too. "I started collecting when I was a kid," Agnew says.

"Everybody's got to have a boat motor collection, right?" he asks, as

he leads a visitor past his.

But

these days, trailers take pride of place. And while Agnew's got a

Colonial-style 'Cottage Home' trailer from 1948, complete with white clapboard

and shutters, the trailers that most stand out are those that are styled

modern.

In the 1920s, trailers were a whole new

building type—though they were rooted in covered wagons, stagecoaches,

sheepherders' wagons, even private railcars. The Curtiss Aero-Car from the

1930s—several examples of which can be found at Butcher's shop—recalls the sort

of railcar that 19th Century barons of industry once used.

In the 1920s, trailers were a whole new

building type—though they were rooted in covered wagons, stagecoaches,

sheepherders' wagons, even private railcars. The Curtiss Aero-Car from the

1930s—several examples of which can be found at Butcher's shop—recalls the sort

of railcar that 19th Century barons of industry once used.

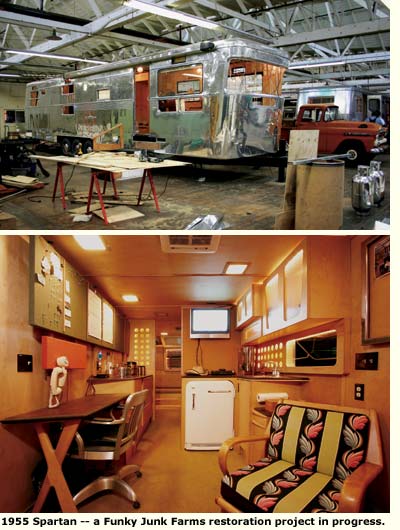

Designers

devised ingenious ways of saving space—hidden storage, built-in banquettes,

tables that slip out of sight, diminutive sinks, showers and kitchens, and

rooms that served for sleeping at night and living during the day. Interiors

often recall 1930s California modernism, or even 1950s tract houses by Eichler, with mahogany plywood paneling, streamlined

cabinetry, and indirect up-lighting. A 1952 Pan-American has sculptural shelves

that suggest the half-living, half-dead creatures seen in 1940s surrealist

painting by Yves Tanguy.

Everybody

knows about the Airstream, of course. The only classic trailer still in

production, Airstreams are polished aluminum, aerodynamically sound, well

engineered, and much loved. Kerrie Aley, who buffs

her aluminum, 1962 Airstream Bambi until it shines like a mirror, loves its

shape, molded interior ("like the interior of a DC-3") and superb

riveting. Aley, who used to design aircraft brake

systems, speaks from experience. "They're built with aerospace

technology," she says. "The thing is just really well-built."

How

Kerrie and her husband Allan Songer came to own their

Bambi shows how much owners love their trailers. Allan first spotted the

trailer in Long Beach, where he and Aley live, and

left a note saying he wanted it. Twelve years later he got a call from its

owner, inviting them over. "She was interviewing us like we were adopting

a pet," Aley remembers. They passed.

At Funky Junk Farms, however, 'Airstream' is almost a

dirty word—not because they're not beautiful, but because they're too common.

"It's like owning a Chevrolet or a Dodge," Agnew sniffs. "We've

called Airstreams 'mainstreams.' " Butcher adds, "We're more into the

rare type that were sometimes built by people who worked in the aerospace

industry, and decided to build their own trailers."

At Funky Junk Farms, however, 'Airstream' is almost a

dirty word—not because they're not beautiful, but because they're too common.

"It's like owning a Chevrolet or a Dodge," Agnew sniffs. "We've

called Airstreams 'mainstreams.' " Butcher adds, "We're more into the

rare type that were sometimes built by people who worked in the aerospace

industry, and decided to build their own trailers."

Funky

Junk Farms has quite a collection of homemade trailers, often based on kits.

One charmer from the '30s has portholes for windows and a rear that pops open

to become a screened porch. But they love factory-built trailers too. Agnew and

Butcher brag about Spartan trailers, with their aluminum exteriors and

wraparound windows. "Spartans are the epitome of the modern," Lum

says.

Then

there are the Shastas, with a cool 1950s look, with

two-tone exteriors. "A lady's trailer," Agnew says of one 1956 model

he's currently restoring for a lady.

Trailers

have a rich history, and the Funky Junk collection covers much of it. Evolving

in the mid-'20s from 'tent trailers,' travel trailers boomed in the mid-'30s.

They provided cheap vacations, and homes for mobile workers and those seeking

work. As the craze took hold, the number of manufacturers jumped from fewer

than 50 in 1932 to 800 in 1936, according to Bryan Burkhart and David Hunt's in

their book 'Airstream: The History of the Land Yacht.' Some trailers were

called 'canned hams,' because of their shape, others 'breadboxes,' for the same

reason. And there were tiny teardrop-shaped 'teardrops.'

By 1940,

after the inevitable crash, the number of manufacturers was down to 40.

Trailers boomed again in the 1950s as new highways made it easier to take to

the road.

Trailers have always been modern in

attitude, even more than in look. "There's this whole on-the-road American

idea of freedom," Aley says. "To me,"

says Agnew, who takes his trailers to the desert and the sea, "it doesn't

matter what kind of trailer you have, as long as you're enjoying the

outdoors."

Trailers have always been modern in

attitude, even more than in look. "There's this whole on-the-road American

idea of freedom," Aley says. "To me,"

says Agnew, who takes his trailers to the desert and the sea, "it doesn't

matter what kind of trailer you have, as long as you're enjoying the

outdoors."

And, as

Lum points out, it's their size that makes trailers seem modern today. 'Think

Small,' the New York Times recently headlined a feature about the

"tiny-house movement," a new generation of modular vacation homes,

"seldom measuring much more than 500 square feet," that are popping

up on mountains and by the ocean.

That's

where Tom Carson comes in. Carson is a young architect whose Marina del Rey

firm does work that ranges from residential to historic preservation—and now

trailers. With Butcher, Carson is inventing "a new, ground-up, free

interpretation of the trailer," he says, for people looking for a second

home, a pool house, or a home office. "It's like a prefabricated

home," he says, "but we're going to leave it on wheels."

"There

are no modern trailers now," Carson says. "That's a huge hole in the

market, and it's what we are aiming at. We're going to revolutionize the

trailer industry with this new piece we're doing."

Today's

trailers lack the style and character of the vintage models they love, Carson

and Butcher say. "We're tired of the look of what's out there now,"

Butcher says. "The style of the trailer has not changed in the last 30

years. It still looks like a 1970s, '80s house." "They lost their

cool look when they started going to fiberglass exteriors," he adds.

Butcher shows off some of the vintage trailers he has

restored and modernized to suggest what his latest endeavor might accomplish.

They've dropped floors to provide holding tanks for water and wastewater, added

air-conditioning, espresso machines, I-pod docks, Tivo,

computer cables, and European cabinetry. They're adding solar panels to a 1952 Spartanette and a vintage Westcraft.

"We try to make it look like it was built in the '50s," Butcher says,

"with a little bit more modern flair to it." "And all the

comforts," Carson adds.

Butcher shows off some of the vintage trailers he has

restored and modernized to suggest what his latest endeavor might accomplish.

They've dropped floors to provide holding tanks for water and wastewater, added

air-conditioning, espresso machines, I-pod docks, Tivo,

computer cables, and European cabinetry. They're adding solar panels to a 1952 Spartanette and a vintage Westcraft.

"We try to make it look like it was built in the '50s," Butcher says,

"with a little bit more modern flair to it." "And all the

comforts," Carson adds.

Movie

stars have used their revamped machines as homes away from home while on

location, and Hollywood writers have used them for offices.

Butcher

may spend his weekdays driving for studios and weekends rebuilding trailers,

but he's never been happier. "That's what we like to do," he says,

"design and build. It's not about the money. It's about building something

cool, something that looks good."

Photos: John Eng. Also by Douglas Keister;

and courtesy Juergen Eichermueller,

PhD, Funky Junk Farms

Splash illustration: Ed Lum

Resources

• Funky Junk Farms is open for tours (by appointment

only) to visitors with a sincere appreciation of travel trailers and all things

vintage. Call 323-309-8087, or e-mail.

Web site: funkyjunkfarms.com

• The Monterey Trailer Park, a Los Angeles designated

historic monument, is at 6411 Monterey Road, in the Los Angeles neighborhood of

Highland Park, a few blocks from South Pasadena and just of the Pasadena Freeway.

• For interesting CD collections of vintage travel

trailer magazines, brochures, and memorabilia, contact Juergen

Eichermueller and view his archive online through allmanufacturedhomes.com

![]()

WHEN 'WHEEL ESTATE' WENT WILD

By Juergen Eichermueller,

PhD

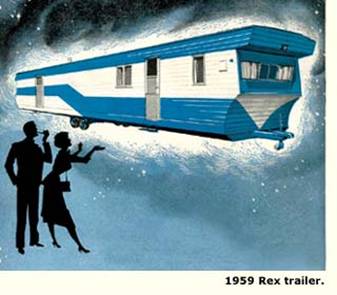

The

'wheel estate' market of the 1950s boasted many bold designs—with big-ticket

price tags to match—that rivalled some of the most

modern site-built homes of the era.

The major difference between the two

living spaces was that the travel trailer, or mobile home (as they were more

commonly called), could be moved, usually by a special moving company, at the

whim of the owner. Whereas the stick-built homeowner was tied down, literally,

to the property on which their house was built, the mobile homeowner could 'get

up and go' to any part of the country, and in any season.

The major difference between the two

living spaces was that the travel trailer, or mobile home (as they were more

commonly called), could be moved, usually by a special moving company, at the

whim of the owner. Whereas the stick-built homeowner was tied down, literally,

to the property on which their house was built, the mobile homeowner could 'get

up and go' to any part of the country, and in any season.

What's

more, if their budgets permitted, mobile folks could cruise the high life,

hanging out at five-star-rated, landscaped mobile home parks equipped with

deluxe amenities, which included heated swimming pools, tennis courts, and

clubhouses.

Of

course, the stick-built house owner did have more living space and larger

rooms. While that was somewhat of a downside for trailer owners, most certainly

didn't feel deprived. After settling into a luxury park, many trailer owners

added on large wood or masonry cabanas, generally the full length of their

trailers. These additions had everything inside them, including sliding-glass

doors, fireplaces—and even wet bars!

Originally,

trailers were manufactured in standard eight-foot widths for ease of towing.

When ten-foot-wide units were introduced in 1954, they were a big hit not only

with mobile home dwellers but also with their designers, one of whom was

Raymond Loewy, the well-known industrial designer. The ten-wides,

as they were called, did require an over-width permit for relocation, and each

state had its own regulations as to how and when they could be moved and the

cost involved.

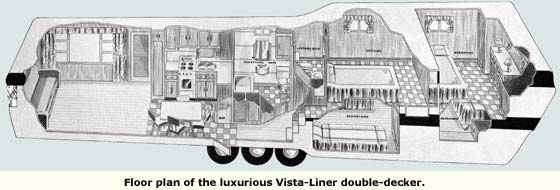

Since

manufacturers were obviously limited in width and length, the designers turned

their attention to creating ingenious and lavish interiors, including two-story

or double-decker models. These two-story trailers featured two bedrooms

upstairs, sometimes with an added half-bath. The downstairs had another bedroom

with a full bath, an ultra-modern kitchen with wall ovens and other chic

appliances, and a comfortable, carpeted living and dining area.

One of the most luxurious double-decker models ever

created was the Vista-Liner by Indiana-based Smoker Lumber Company. Literally a

land yacht, the Vista-Liner came in two lengths, 45 and 50 feet, and featured

four bedrooms, two baths, oak flooring, and various other modern

accessories—and sold for a whopping $25,000 FOB! Meanwhile, in Florida, a new

three-bedroom, 1.5-bath house on a lot was selling for under $10,000!

One of the most luxurious double-decker models ever

created was the Vista-Liner by Indiana-based Smoker Lumber Company. Literally a

land yacht, the Vista-Liner came in two lengths, 45 and 50 feet, and featured

four bedrooms, two baths, oak flooring, and various other modern

accessories—and sold for a whopping $25,000 FOB! Meanwhile, in Florida, a new

three-bedroom, 1.5-bath house on a lot was selling for under $10,000!

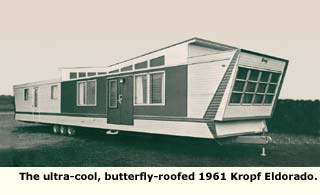

Smoker

was not the only manufacturer that produced such high-priced wheel estate.

Another Indiana company, Kropf, came upout with a ten-wide mobile home called the Eldorado that

boasted an actual butterfly roof (ala the Palm Springs Alexanders)

with clerestory windows in the living and kitchen areas that compared in design

with some of the country's best site-built homes. "Supremacy in regal

luxury, styled for lasting beauty," boasted Kropf's

ads. The price for this regal beauty ranged from $10-15,000.

Pan American was a well-known West Coast manufacturer

that produced mobile homes in the same price range as Kropf,

but with the sunny California look of sliding-glass doors, large windows

throughout, and central air conditioning.

Pan American was a well-known West Coast manufacturer

that produced mobile homes in the same price range as Kropf,

but with the sunny California look of sliding-glass doors, large windows

throughout, and central air conditioning.

Two

other California manufacturers, Budger and Trailorama, built eight- and ten-wide mobile homes that

expanded their widths to 16 and 20 feet wide, respectively, when parked. Decorated

in style, from California modern to French provincial, their interiors featured

all of the comforts one could imagine: fireplaces, ultra-gourmet kitchens, and

up to three bedrooms and three baths with dressing rooms. Their prices?

$10-20,000.

Who

bought these trailers? Who could afford them? Generally they caught the eye—and

pocketbooks—of retired doctors, lawyers, businessmen, and others in the golden

'50s who appreciated not only the regal design of the mobile home but also the

plush country-club-like lifestyle of the upper-end mobile home park.

Trailer

trash? Not hardly!

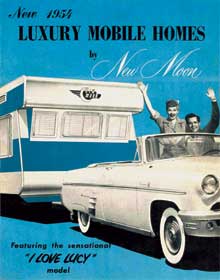

Powered by Lucy

TV stars Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz brought

respectability, fanfare, and a surge of sales to trailers and their industry

with the 1954 comedy film 'The Long, Long Trailer,' directed by Vincente Minnelli. The couple's adventures were centered

around their new vacation home on wheels—a streamlined, yellow-and-white,

36-foot 1953 New Moon trailer from the Redman Trailer Company.

TV stars Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz brought

respectability, fanfare, and a surge of sales to trailers and their industry

with the 1954 comedy film 'The Long, Long Trailer,' directed by Vincente Minnelli. The couple's adventures were centered

around their new vacation home on wheels—a streamlined, yellow-and-white,

36-foot 1953 New Moon trailer from the Redman Trailer Company.

The

excitement that surrounded the 'I love Lucy' trailer was the best thing that

could have happened to any trailer manufacturer in the 1950s. What's more,

trailer folks (as well as parks) were portrayed as nice and pleasant—never as

'cheap.'

'The

Long, Long Trailer' became MGM's bestgrossing comedy

up to that point and transformed Redman overnight from a small regional outfit

(building one or two trailers a day) into one of the nation's largest mobile

home manufacturers (with five or six factories, producing hundreds each day).